A parable.

One day I went in to my boss with a breakthrough idea.

“Boss! I found a way to make money off of other people’s websites, the best content websites in the business in fact.”

“Really?” he said. “Tell me more.”

“We can actually place ads on their site without them agreeing to it. In fact, they don’t even know we’re doing it.”

“You mean when I click on a link to a company’s website they would see OUR ad?”

“That’s right,” I said. “Right at the top. We can even make it look like it is part of their site!”

“Are you telling me we could even do this to our competitor?”

“Anybody. Even a competitor.”

“So you’re suggesting we make money off other people’s work? We display our ad to their huge audience on their copyrighted content and we don’t have to spend a dime creating content of our own? We don’t compensate these people for putting ads on their site, we don’t even involve them in the decision? And we can re-direct their site visitors to our website?”

“Not only can we do it, I started doing this yesterday!”

My boss glared at me over the top of his glasses. “In that case,” he said, “you’re fired.”

Of course I made up this bizarre scenario. Who would ever do something like that?

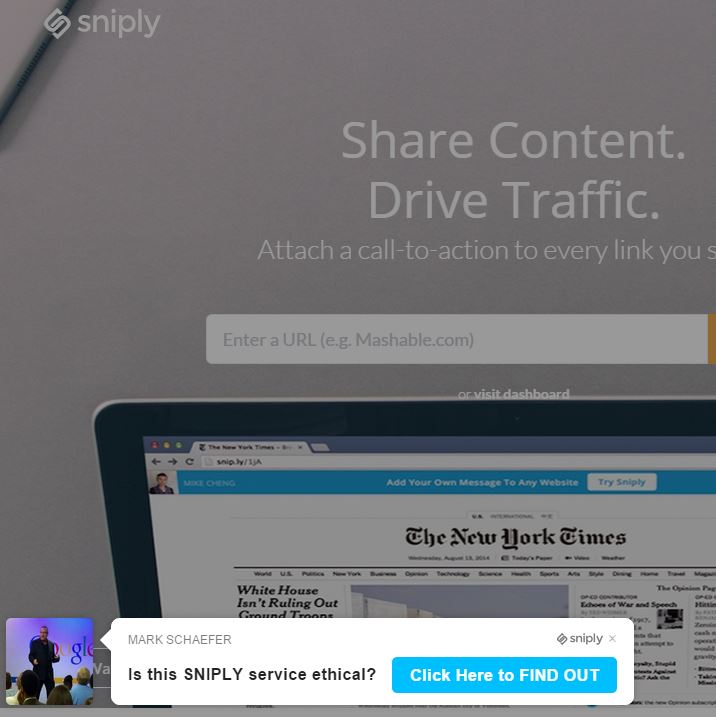

But in fact, this is what is happening right now via a web service called Sniply. It provides a grotesque example of how desperate even reputable digital marketers have become in an era of ad blocking.

The story of Sniply

It works like this.

I sign up for a Sniply account and create an ad. I find a piece of excellent, relevant content that I want to share with my audience, paste the link into the menu, and generate a preview of what my ad will look like on the target site. A link is provided and when the link is shared across social media, the viewer sees my ad as if it is native to the target website.

Sniply works by subscription, the more you pay them, the more ads you can generate and the bigger the ad you can place on a competitor’s site.

Here is what my blog looks like when a company places a Sniply ad on it:

The only way I would know this ad is on my site is if I happen by chance to click on a Sniply-related link. When another company sets an ad on my site, I don’t get any notification about it at all.

Who is this company placing an ad on my site? I have no idea who Colibrio is (could you even see they sponsored the ad?) It turns out that they could be considered a competitor.

I sent them an email, several tweets and a Facebook message asking them to remove the ad and I did not get a response.

As I was experimenting with this, I demonstrated how I could easily hijack somebody else’s trusted website for my own commercial gain. For example, I could promote my value as a keynote speaker on Chris Brogan’s website. With Sniply I could draw them away from Brogan to me if they are looking for a keynote speaker …

I did not actually post this and of course I would never do something nefarious like this … but of course many people are now doing this sort of thing every day. In fact, draining people away from your site is what the service is intended to do. Sniply clearly states this objective in their training video and a company founder plainly stated in this interview that his goal is to create a financial return from other people’s content.

Through Sniply, there is virtually no limit on what ads might appear on your site — a competitor, a political candidate, a hater, a pornographer. Sniply does lightly audit its users, checking on ads after they receive 1,000 clicks. The company told me their click through rate is less than 1 percent, meaning an ad would have to appear on your site at least 100,000 times before it would be possibly flagged as unethical.

Is Sniply legal?

Sniply lists an impressive group of customers on its site: HubSpot, Deloitte and Salesforce to name a few. But there is some question as to whether this process is even legal.

In an analysis on Plagiarism Today by Jonathan Bailey, the author maintains that Sniply is “unethical” and possibly illegal due to:

- Trademark Infringement: If users are led to believe that the site endorsed or had a relationship with the Snip.ly user that didn’t exist, it could create a trademark issue.

- Copyright Infringement: It could be argued the Snip.ly creates a derivative work based on the original site, creating a copyright infringement.

- Misappropriation: By using the name, likeness and other elements of a person in a way they don’t permit, framing could give rise to a misappropriation claim.

Bailey points out: “All of these legal issues (and more) came up in the case The Washington Post v. TotalNews. In that case, Total News was using frames to display their logo and ads above content provided by The Washington Post (and other news sources). The case, however, was settled out of court before a ruling was handed down. In the settlement, TotalNews agreed to cease all framing activities and, instead, only link to the news stories.”

But aren’t you getting exposure?

The defenders of the practice point out that you may be getting new incoming traffic from the companies advertising on your site. Isn’t there fair value in that?

But not everybody is so enthusiastic about this trade-off. In a recent Facebook post, Digital strategist and entrepreneur Matt Ridings expressed outrage at the idea of unwittingly hosting unwanted ads for “exposure:”

The question is this: If I pay for hosting. I pay for design. I pay with my time and hard-earned knowledge to share original content. Should I have the right to dictate how that content will be consumed? What it will look like on a mobile device? Whether my content is associated with advertising or not? Whether or not I want to ‘barter’ with people to ‘advertise’ my content for me and get something for themselves in the process?

Matt went on to provide an example:

Imagine you write a book. The publisher, without asking or putting into the contract, inserts an ad into the book every few pages. Would you have negotiated the same amount for the book deal? Would you be pissed? I mean, their book is still being sold right? Of COURSE they should be pissed, because they designed the book to be experienced in a specific way that they felt best benefited their readers/audience. Now the author, like it or not, is associated with an advertising based revenue model …

Isn’t this the same as curation?

What’s the difference between somebody curating your content (and slapping their ad on it) and Sniply? Marketer Meg Tripp answered this eloquently in a Facebook stream on this subject:

I get that “curation” is the buzzword people invoke when they do this, but to me, curation means thoughtfully sharing content by others with full attribution and credit, and a link to the original property — IN ADDITION to creating your own valuable content. Not slapping your CTA on top of someone else’s stuff and calling it a day. That does nothing to build your credibility in my eyes. It doesn’t make you an expert in your field, it makes you a decent Googler. Or an Other Peoples’ Content Marketer.

Also, though I just used it, I’m getting tired of the term “content”, too. It’s not the stuffing inside a pillow, it’s stuff that takes hard work and thoughtfulness to create.

The other side of the story

The people over at Sniply have been working hard to develop their platform and I wanted to give them an opportunity to tell their side of the story. Here are responses from one of the founders, Mike Chen:

1) You are allowing people (even competitors) to post ads on our sites without our consent. Do you see this as being ethical?

Sniply is a technology that can be used ethically or unethically. The tool itself has benefited both content sharers and publishers alike through increased traffic for both parties. Sniply rewards content sharers for sharing and results in additional traffic for the publisher. Abuse and misuse is possible but we have both manual and automated measures for limiting misbehavior.

2) I charge companies to place ads on my site. If you place ads on my website are you willing to share your subscription revenue with content providers you rely on for your business model?

While in the future I do hope that we can grow to a point where we can afford to consider a profit share model, however at this time we are still an early stage startup without the means to do so. What publishers get through our technology is the additional traffic through incentivized sharing, and traffic is revenue in the world of content.

3) I have done some experiments and have shown how I could easily hijack a competitor’s site with messages of my own or even pornography. What is keeping anybody from abusing this service to harass and bully people?

We have manual and automated detection for spam and abuse. Once an account reaches a certain level of activity, usually around 1000 clicks, their links are processed through our detection systems. We match Sniply messages with a list of malicious keywords to prevent harassment. Accounts are quickly banned when they are caught abusing the system.

4) I want to opt out of this service. How do I do that?

Anyone can easily opt out of Sniply and there are several ways to do so listed here http://snip.ly/publishers/

Note: To opt-out of Sniply this way, you actually have to sign-up for the service first. Here is another option. You can install this free plug-in to keep Sniply ads off your site.

A final word

The primary issue being obscured by Sniply and its advocates is that it’s not unethical people who make this flawed. The business model itself is flawed. The company is collecting money to allow anybody to paste commercial messages on your site without your knowledge or consent. The objective of these ads is to skim visitors, customers, and revenue away from you so that ultimately they can make a financial return from your hard work.

With the turmoil in the advertising industry, it’s unlikely that Sniply or similar services are going away soon. In the end, you will have to decide whether the possibility of increased traffic is worth the risk of giving up control of what is displayed on your website.

But the essential point is, it should be your decision.

Nobody should EVER be forced to display ads from strangers on their website without their knowledge, consent or compensation. Period.