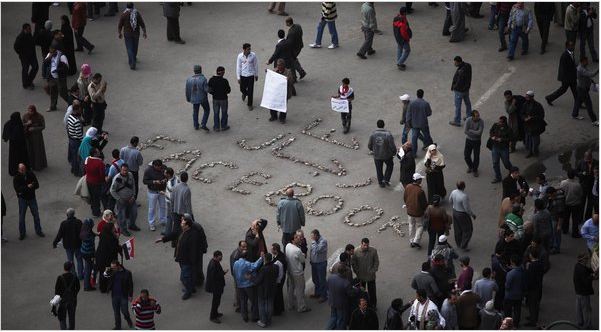

As protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square faced off against government forces, they were prepared with this Facebook lesson from supporters in Tunisia: “Advice to the youth of Egypt: Put vinegar or onion under your scarf for tear gas.”

This exchange (as reported by the New York Times) was part of a remarkable two-year social media collaboration that began with bloggers calling for labor strikes and resulted in an energetic youth movement that is toppling dictators.

And I can’t help but wonder in a very public way, was I wrong?

Just a few months ago, I declared in “Is Social Media Creating a Generation of Cowards?” that I agreed with Malcom Gladwell’s now famous contention that “the revolution will not be tweeted.” He compared the heroic activism of the Civil Rights Movement to the “slacktivism” of today’s Facebook culture where involvement ends at “liking” a page. He boldly stated — and I agreed — that the weak connections and lack of organizational structure on the social web was unlikely to enable radical social change.

Was I wrong?

Yes, I was. I had completely missed a big idea that had nothing to do with organizational dynamics: Social media can be used to build and ignite a brand — even when the product is a political revolution! In fact, marketing has played an extremely important role in the shifting Arab political landscape.

Like the rest of the world, I was fascinated by the courage and discipline of the youth movement in Tunisia, Egypt and beyond. I’ve read as much as I could consume and although I do not have the benefit of a first-hand experience with the situation, I think that without question, social media enabled the movement, united protesters, and kept the revolutionaries one step ahead of the government counter-measures.

Like the rest of the world, I was fascinated by the courage and discipline of the youth movement in Tunisia, Egypt and beyond. I’ve read as much as I could consume and although I do not have the benefit of a first-hand experience with the situation, I think that without question, social media enabled the movement, united protesters, and kept the revolutionaries one step ahead of the government counter-measures.

If you have any doubt about the courage displayed by the protesters or the critical role of Facebook and Twitter, click on the image above and watch a short video about the “Facebook Flat” in Cairo.

While the protesters relied on classic tactics of nonviolent resistance, they also owe their success to marketing savvy borrowed from Silicon Valley.

The mastermind of the movement was Wael Ghonim, a 31-year-old Google marketing executive. Inspired by bloggers such as Ahmed Maher, Ghonim had little experience in politics but an intense dislike for the abusive Egyptian police. While the underground revolution had actually been fomenting since 2005, it needed a business perspective to get off the ground.

“I worked in marketing,” he said. “And I knew that if you build a brand you can get people to trust the brand.”

The marketer’s first campaign was a Facebook group called We Are All Khalid Said, after a young Egyptian who was beaten to death by police.

Ghonim filled the site with video clips and newspaper articles about police violence. He repeatedly hammered home a simple and memorable brand message: “This is your country.”

Engaging the “customers”

He eventually attracted hundreds of thousands of followers to the site and the “brand” actively engaged with them. For example, when organizers planned a “day of silence” in the Cairo streets, he polled users on what color shirts they should all wear — black or white. Finally, after the Tunisian revolution on Jan. 14, Ghonim used the Facebook site to mobilize support for a public protest. He asked for a pledge from 50,000 followers to turn out in protest. More than 100,000 signed up.

“I have never seen a revolution that was pre-announced before,” he said. Or, another way to look at it: He was launching the brand.

When a protest started to become a movement, best practices were shared via Facebook from counterparts in Tunisia and Serbia. Young Egyptian and Tunisian activists brainstormed on the use of technology to evade surveillance, commiserated about torture and traded practical tips on how to stand up to rubber bullets and organize barricades … primarily over social media platforms like the April 6 Movement Facebook page and Twitter.

On February 1, 2011 (the day the Internet was turned back on), Egypt gained 100,000 new Facebook users.

Al-Jazeera, a news channel with an agenda, added drama and emotion to the brand by broadcasting heroic stories and swelling theme songs. The revolution became an ongoing music video.

Entering new markets

Like all popular brands, this is already reaching into new markets like Libya. Where could it go next to reach new customers? This entry from the Youth Movement Facebook page may provide a clue:

So that’s the story of how I was wrong … and so is Gladwell because he missed this point, too. We were both looking at historical events and organizational dynamics, not realizing that the new social media business models can be applied to a wide variety of human activities, even something as unlikely and startling as toppling a dictatorship.

I realize my characterization of this revolution as a “brand” is unorthodox and I don’t want to come across as disrespectful in any way. I would never diminish the truly heroic personal efforts and sacrifices made in the face of real danger.

But I also think it’s important to recognize these new communication and societal dynamics and how social media will be used in ways we could never imagine. Truly, the revolution is just beginning. For all of us.