By Kerry Gorgone {grow} Contributing Columnist

The Internet is a bit like the Wild West when it comes to protecting intellectual property and a new law makes it even a little more difficult to lay claim to your images without some proactive measures on your part.

The controversial Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act, which just received royal assent in the U.K., permits the use of “orphan works” — copyrighted works for which the owner cannot be identified. In most cases, the owner is dead, although it’s also possible that he or she simply has no interest in laying claim to the work.

Permitted uses under the new law would include digitizing archival library collections of unpublished works for purposes of preservation, but the law also allows commercial, for-profit uses of these works, such as advertising.

Photography groups vehemently opposed the legislation on the grounds that they stand to lose ownership and control over any images they post online. Critics have compared the law to the sweeping changes that Instagram made (and later unmade) to the app’s terms of use in December 2012.

Artists and photographers everywhere need to take proactive measures to protect their creative works, placing watermarks on images prior to uploading them online, and populating metadata with ownership information.

The U.K. media is also recommending that photographers and artists register each individual work with the U.S. Copyright Office or the PLUS Registry in the U.K. to ensure that they are identifiable. This way, even if someone could strip identifying information out of an image and repost it online, an interested owner can always come forward to claim their work. Many have cited the cost and time required to register each individual work as prohibitive, but at the moment, there aren’t many options.

Individual authors / artists registering through the U.S. Copyright Office could try registering works as a compilation, provided they published them all within the same year. (37 CFR 202.3(b)(10)) The filing fee for registering groups of photos is currently $65. At minimum, this reduces the likelihood that a work will be considered “orphaned” in the first instance.

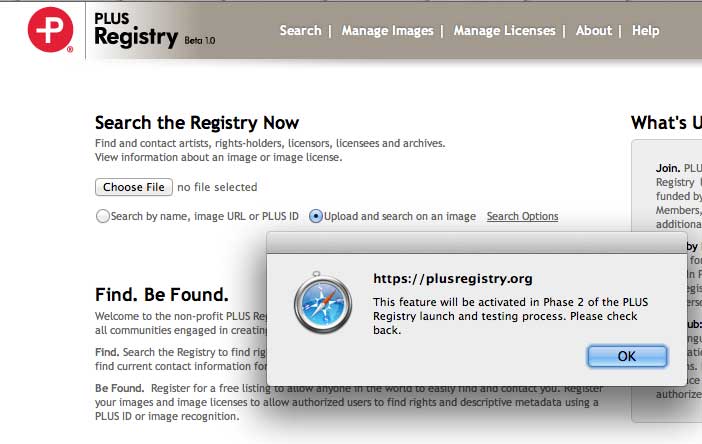

Obstacles abound for copyright holders, including the fact that the U.S. Copyright Office does not offer a reverse image search. In the U.K., the PLUS Registry only holds names, and the “upload and search on an image” function does not yet work. Still, anything is better than nothing, given that the law has passed.

Another important thing to note is that the U.S. Copyright Office saves images for only ten years, unless the copyright holder pays an additional $470 for “full-term retention of a published deposit,” so the value of registration after that point is questionable.

One thing photographers can do is monitor Google for uses of their copyrighted works. Google’s sophisticated search technology does permit reverse image searches, so users can upload their copyrighted image and see matching images identified by Google. This will help copyright owners to detect infringing uses, so they can assert their rights against the infringing party.

As theoretically devastating as this development is for photographers, I really think that most works affected will be works no owner will ever claim; images that previously could not be used because of a potential copyright claim that would never materialize.

Companies don’t want legal headaches anymore than you do. They’re unlikely to intentionally use works that someone might sue over. Given the huge body of available images, there’s no reason to think they’d elect to steal a copyrighted work when they could find (or create) any number of suitable images for advertising purposes.

Bottom line: protect yourself to the extent you can. Wouldn’t you do that anyway?

Kerry O’Shea Gorgone, JD/MBA, is an attorney who teaches New Media Marketing in the Internet Marketing Master of Science Program at Full Sail University in Winter Park Florida. Follow her on Twitter: KerryGorgone

Photo courtesy Flickr Creative Commons umjeandoan