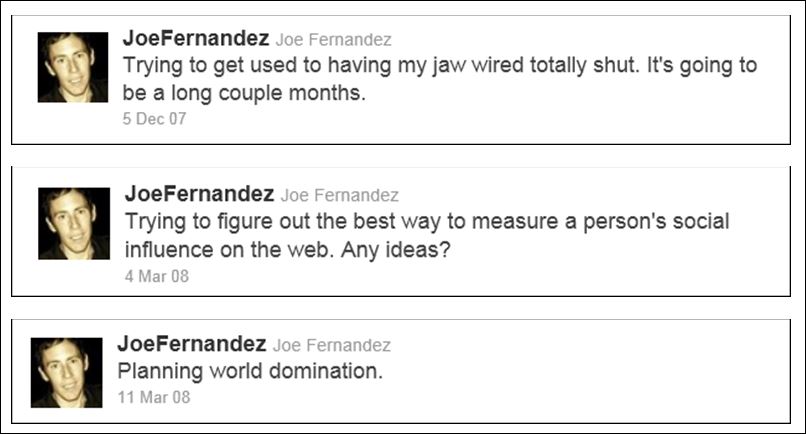

The genesis of Klout circa 2008.

Yesterday Lithium announced it had acquired Klout for nearly $200 mm in cash and stock, closing the door on the “start-up” chapter of Klout’s six-year history.

Klout Founder Joe Fernandez spoke to me shortly after the public announcement and discussed his emotional journey in founding a company, fighting for funding and legitimacy, building an enterprise, and finally positioning his life’s work for a new era of growth.

Whether you love Klout or hate the idea of social influence metrics, the story of Klout’s unlikely start and ultimate financial victory is fascinating.

As a special bonus to {grow} readers, following the interview with Joe, you’ll find a free excerpt from Return On Influence with the story of how a first-generation Cuban immigrant went from selling CDs in his college dorm room to becoming America’s newest multi-millionaire.

This interview was conducted about four hours after the Lithium announcement was made official.

Schaefer: Are you exhausted right now?

Fernandez: Definitely. Exhausted and exhilarated. This was an intense process and an intense decision. But I also feel a tremendous amount of excitement about what is ahead. With the opportunity ahead of us, I am tired at the moment but totally re-invigorated and happy.

Schaefer: In all my years in business, I have never met a person more focused and passionate about making a company come to life than you. I have to imagine there are a lot of emotions going on for you today as your baby is adopted by another company.

Fernandez: Having something you have worked on for so long be valued by the outside world is certainly very rewarding for all of us who fought through this whole process.

I feel an intense amount of gratitude to the team, even the haters out there who helped turn Klout into a better company. And of course for our customers and our millions of supporters — we have become a world brand because they cared so much about the company.

I have mixed emotions after such an intense process. Really, my emotions have been swinging hour by hour.

Schaefer: You’ve had an incredible opportunity to personally nurture your business idea for six years. How is Klout different today than what you first envisioned? In other words, what is the most surprising aspect of the company you could not have foreseen when you started out?

Fernandez: I never, ever imagined the horizon of opportunity that was set before us,

When I started out, I thought my idea could help people make some sense of social media. I figured at some point we would have 10 people working for us and then maybe Twitter would acquire us.

But today we are a worldwide brand and now associated with a company about to be part of an IPO. We have come a long, long way.

The idea that we could be part of a system now with a real possibility of changing the way consumers and brands interact with each other on a massive scale is beyond anything I could have imagined just a few years ago.

Schaefer: The inherent value of Klout is its ability to provide a relative measure of a person’s ability to move content. A blunt instrument, but obviously useful in some cases. You once stated a vision of a Klout that connected the dots on dozens of content platforms but that effort stalled. For example, any consideration of self-hosted blog content is absent from the Klout equation … that limits the scope and usefulness of the measure. With the new resources at your disposal will you get that back on track?

Fernandez: We have always had a desire for data dominance, to pull data from many, many sources — wherever these important conversations might be. We have not diverted from that long-term vision but we had to re-prioritize within the context of our path and the limited resources that we had. At some point you need to balance pure research with commercial interests.

The deal with Lithium is exciting because we now have the legroom to fulfill that vision and really build a holistic view of who a person is across a wider span of communities.

Schaefer: Do you have regrets along the way?

Fernandez: Oh yes of course. There are a million little things I could have done better. Like most entrepreneurs, I’m hardest on myself.

This was my first time really managing a business of any kind, at any level. I was struggling to learn everything. Literally everything. As a start-up you pretty much have to have your hand in everything and I didn’t know everything! There were painful lessons every day. I learned fast but of course I could have been better in practically every area in some way.

Schaefer: When companies go through growing pains like that, a founder will often bring in a more experienced executive to lead the company through its growth phase. Did you ever wonder if you were the right leader for Klout as it began to grow?

For me, this has never been about me being a CEO to fill out a resume. This journey has been about only one thing — fulfilling the vision, whatever it takes. To be successful, you have to put your ego aside.

Throughout this process I had periods of self-reflection when I tried to determine if we had the right pieces in place to fulfill the vision, and questioned everything, including my role at the company.

I determined that yes, I was the best person to lead this company for one reason: I am the person on this earth with the most passion to fight through everything and make it work. I have the passion. I am am the right person.

But this was an on-going dialogue, an active decision re-visited through each stage of the company’s growth. This was never about having five or six good years, it was about staying true to the vision and building a company that lasts.

Schaefer: Six years ago you were manually calculating Klout scores, sleeping on couches and begging for money from friends to keep your company afloat. As of today, you are a multi-millionaire. What is the first thing you are going to splurge on?

It’s really funny to have some money now after all these years. Seriously, I don’t even know what to do. I keep thinking that it might be fun to have jet skis. That is the only thing that has popped into my mind.

I’m hoping to take a break soon and travel with my wife. She really deserves it. So we will do some traveling.

I have money but I don’t feel that different. I feel just as scrappy. I’m the same person.

BONUS CONTENT – Free excerpt from Return On Influence ,

,

“The story of a start-up”

The idea for the first attempts at a social scoring algorithm can be traced to a bored, frustrated young man sitting for hours on end, playing on his computer, and exploring social media sites … because at that moment in his life, it was the only way he had to communicate with the outside world.

At the age of 17, Joe Fernandez, who was to become the founder of Klout, was suffering from intense head and stomach pains. He was diagnosed with a rare medical condition that could only be resolved by jaw surgery … and literally wiring his mouth shut.

“I put the surgery off for years,” Fernandez said. “I waited, hoping technology might get better and there would be like a lotion I could put on or something! But, in 2007, the pain was getting worse and I ended up having the surgery. I thought I could just power through it, but it was pretty hard. In fact it was much harder than I ever imagined. My jaw was wired shut for two months so to communicate, I either had to write stuff down or go on Twitter or Facebook because nobody could understand my mumbling.

“So I had this stir-crazy, drug-induced period of time in my 350-square-foot apartment in New York City. I was thinking about these social media tools I’m using to communicate, which at this point, I am pretty much totally relying on for my life! And that intense experience really changed the way I thought about these tools. I began to notice that the people who trusted me the most would instantly follow what I was saying. I could tell them my opinion and it would have some sort of impact on them.

“The other point that was interesting was that all this data was out there — the fact that Twitter and Facebook had an API and all of these other services had an API was pretty cool to me.”

Locked up in his apartment for seemingly endless hours, Fernandez began to plot his ideas on an Excel spreadsheet … every social network he could find, every possible activity on those platforms that might signal influence. He saw patterns in the cells. Connections. And the connections turned into equations.

An idea for a new company, a new way of marketing, was forming in his head, but the concept was really the culmination of a lifetime of entrepreneurial experimentation and failure.

The young entrepreneur

Fernandez grew up in a family that appreciated the value of taking a gamble. His grandfather was a hotel and casino manager in Havana who moved his family to Las Vegas when the Communist Revolution shut down the gambling business in his country. Joe’s father continued the family tradition, managing casino properties in Las Vegas, Lake Tahoe, and Atlantic City. Young Joe observed his father skillfully courting and befriending big spenders as a marketing manager for Caesar’s Palace, a lesson in networking that would be crucial to his development as an entrepreneur who had to call in a lot of favors to help his business survive.

As a teen, Fernandez envisioned a career in the casino business but also had an entrepreneurial bug from an early age. “Even in high school I had a lock on the used video game market,” he said. “And in college I marketed music CDs through the players on the football team.”

Fernandez attended the University of Miami (FL) but couldn’t settle on a career choice. “I changed my major like 20 times,” he said. “I finished with an emphasis on economics, finance and computer science, but I never actually graduated. You needed 126 credits and I left with 140 in four years, but it was all over the place because I was always working on some side business and making pretty good money at it, too.”

Fernandez had an opportunity to study English and political science at Oxford University for a year before landing his first job in 2000 with a technology consulting firm in Los Angeles. Little did he know that he was on the brink of a serious and extended personal collapse.

Within a few months of beginning his first real job, the white-hot Internet boom turned to bust and Fernandez was among the thousands of eager computer coders and tech consultants looking for work again.

After 10 months, he could not find meaningful work of any kind and took a run at a childhood dream by using his meager savings to start a skateboard company … which failed in short order. His money was running out, he was on the verge of being evicted from his apartment, and his career prospects were bleak. To make ends meet he took an entry-level technical support position. He hated the job, but his life was about to change for good.

Founding his first company

In 2002, Fernandez met a retired psychologist who had an idea to streamline the way that public schools kept up with newly-regulated reporting requirements for students. Fernandez, with the help of a few friends, started a company to build a computer program that would help school districts manage this paperwork-heavy process. As soon as the start-up had its product ready, it landed its first customer – the gigantic San Francisco Unified School District. With that bright start, they could not have foreseen that this would be their last customer, too.

“After that first sale, I really had visions of being a millionaire in a few months,” he said. “But we could never sell another system. We couldn’t figure out how to deal with the bureaucracy and politics of the school systems. We pushed and pushed for 18 months, boot-strapped it, and used every penny we had, but it became apparent that we weren’t going anywhere with this idea.”

In the end, the company salvaged its work by licensing the technology to other school system vendors who tracked lunch programs, special education efforts, and other student activities – a system that is still in place and generating revenue across 5,000 U.S. school districts.

Now 25, Fernandez was out of work once more, but had several new weapons in his personal arsenal. He had learned what it was like to bootstrap a new business, lead a team of business partners, deal with the highs and lows of entrepreneurial life, and build a marketable product based on massive amounts of data. And with the school project licensing deal, he finally had a little financial breathing room for his next venture.

With nothing left for him in California, Fernandez decided to follow a lifetime dream and move to New York City. He was soon using his natural networking skills to become part of the city’s vibrant tech start-up scene.

“By late 2006, I had a couple of ideas,” Fernandez said. “One would have been like a Foursquare/mobile kind of thing. I had another idea around restaurant reviews. I actually went to India, hired a team of developers, and tried building a few ideas on the side, but nothing really stuck.”

The Birth of Klout

“Then in 2007, I had the jaw surgery. And my thinking about a new business model started to change a lot.

“I had so much time on my hands in my apartment, and as I experimented with these social media ideas, I started hacking something together that would be the first algorithm for influence. This idea for Klout just stuck with me. That was always the name … Klout. It was more about the idea of quantifying influence than the technology, and I couldn’t shake it.

“When I got un-wired, I did some consulting but I was always working on this idea. I guess it became an obsession. I just couldn’t stop thinking about the possibilities and realized that this was something I had to do. So in August of 2008, I quit everything I was doing and went all-in on Klout.”

His first priority was to find a technical team to activate his idea but he couldn’t afford anybody in New York and he couldn’t convince any of his friends to quit their job and bootstrap, so he turned to a group of developers in Singapore who had authored some of the software used by the real estate venture.

“They had actually reported to me in another venture and I knew them really well, so I decided to hire those guys to help me with the first version of Klout,” he said. “The time difference made it really hard to get anything done so I went to Singapore for several months and crashed at the developer’s house and worked in their office whenever I could to help build the first platform for Klout.”

In less than six months, the software was ready to go and the first version of Klout was launched on Christmas Eve, 2008.

“It was pretty funny at the time,” Fernandez said, “because, if anyone registered I had to manually calculate their score myself! So it was definitely a mess … but people were interested. The moment we launched, I tweeted my score. This caught the attention of some of my friends in New York and it started to catch on among a small but rabid group of fans. To them, Klout was like ego crack.

“Just one week after I launched I was asked to present the idea at an important tech meet-up in New York City. I mean it was kind of ridiculous to have this opportunity right out of the box. What was I going to say? That I had developed an algorithm that’s going to decide how important everybody in the world is? How could I possibly say that? I’ve not achieved anything that would allow me to make a claim like that. There’s nothing on my resume that says I’m the one that should be allowed to make that decision.

“So here is what I told the crowd about market influence: Everybody who creates content has influence and with Klout I want to understand who they influence and what they’re influential about. It’s not about the A-list any more. It’s about every person. And that resonated with the people in the audience. Klout was very crude back then – just one page really — but I think they could see the vision that was behind it.”

In early 2009, Fernandez returned to Singapore to supervise the next evolution of the product. Accompanying him was his friend Binh Tran, a cofounder on the education software startup, who quit his job to join the Klout venture full-time. Tran became the Chief Technical Officer for Klout and continues to shepherd its development.

Klout on the Ropes

Between sleeping on the floor with his friends in Singapore and bootstrapping the new business from his tiny apartment, Fernandez was able to finance the first 18 months of the venture out of his own pocket. But he would soon need investors if Klout was going to avoid a death spiral. He needed to call on all of his formidable networking skills just to give the company a chance to survive month-to-month.

“It was touch and go for a long time. I couldn’t have made it through this period without a lot of help,” he said. “The guys in Singapore and the company hosting us trusted me enough that they let us ride on our bills for a really long time. They would threaten to shut us off and I would come up with $10,000 or $20,000 and we’d be cool again. If we would have had to pay them the full amount every month … well, it wouldn’t have happened. I had to use all of the social and political capital I had and I spent every penny of the money I had made from both of my previous companies and still, we were barely getting by. So I needed to meet people who could help. I decided that I needed to go to South by Southwest.”

South by Southwest (SXSW), the annual tech event in Austin, TX, is considered the World Series of Start-Ups. Tens of thousands of innovators and investors descend on the city each March hoping to be the next big thing – or to discover it. During a stint in Singapore, Fernandez applied for a spot on the one of the highly sought-after Accelerator Programs, where a panel of judges helps find the coolest new start-up or web-based application. The Klout idea was accepted into the showcase. Fernandez was going to have his chance.

“This was a huge deal – an amazing opportunity. We needed this exposure because at that point we had just launched the company and literally had no money– I was begging and borrowing to keep Klout alive.

“I knew that once I got in front of that huge South by Southwest crowd with lots of investors and told them what we were doing, that we would have funding the next day and everything will be perfect from there. So we show up … and we’re given the 8 a.m. slot on the very last day. Not a popular time! The whole time I was there, all I did was stay in my hotel room to do coding and practice my two-minute presentation. That’s all the time I had to save the company — two minutes! So I had all of this build-up and when I arrived, there were four people in the audience. The microphone wasn’t working. And the judges – Guy Kawasaki, Don Dodge, and Nova Spivack – are like … yeah, this is a dumb idea … NEXT. This was going to be our coming out party and … total crickets.

“We were out of money. This is early 2009 and the economy was terrifying. We built our platform initially on Twitter and at that point people are still trying to decide if Twitter is a joke. I’m beginning to wonder — can I really do this?

“As a last-ditch effort, I e-mailed the judges from the South by Southwest session to thank them for their time and their feedback and told them that I hoped we could talk some more sometime soon. Nova Spivack replied to me and said he thought our concept was interesting and offered to buy me coffee if I was ever in San Francisco. I replied back that I was going to be there the next week, even though I had no specific plans to be there. We met and I told him what I was thinking about Klout and what I was working on and he thought it was really cool. He said he wanted to invest … and wrote me a check that day. Our first angel investor! He also introduced me to an attorney to incorporate the company and also had me meet with a second investor. So we had our financing. We could keep going, and slowly begin to grow.”

The breakthrough

Money troubles continued to plague the young company despite the welcome infusion of cash. Ten months after the meeting with Spivack, he had no further interest from investors. “We were running on fumes the whole year,” Fernandez said.

“I pitched over 100 angel investors and some would say, ‘that’s a dumb idea, Twitter’s going to disappear.’ Others would say, ‘this is a good idea, you should focus on the data side.’ So, I would revise my pitch for the next investor and focus on the data side and then they would say, ‘no, you should focus on the advertising piece,’ so then my pitch would change for the next presentation.

“I finally decided I needed to focus on my own vision for Klout and I eventually attracted 37 angel investors, which is a lot — I don’t know of any start-up that has that many. But we didn’t attract any of the big names or these big-shots that other tech companies have as investors. We sort of have this group of random, organic, long-term investors — and we raised $1.5 million. That is what really got us going. We were able to hire a few people and move into an office in San Francisco.”

The entrepreneur’s networking instincts were keen, even when it came to the location of the new company offices at 795 Folsom Street – the site of Twitter’s headquarters.

“With our business model,” he said, “it was important to be best friends with the Twitter guys.” His theory was that by hanging around with executives at one of the hottest tech companies around, some of the magic could rub off. “I wanted to see who was visiting the Twitter office so I could pounce on them and meet them. And then I would invite them to swing by and visit us next door at Klout.”

With an increasing number of fans in high places, the company easily raised another $1.5 million in May of 2010 and seemed to be riding the wave of social media popularity.

“Social media and Twitter blew up and the economy started to get better,” he said. “Everyone, it seemed, began to realize that what we were doing might be important and we started to get a lot of attention from the institutional VCs. In December of 2010 we closed on $8.5 million from Kleiner Perkins. Basically they are the Stanford or Harvard of venture capitalists. So to go from no interest in us at all to having the best VC in the world in less than a year was pretty exciting.”

Momentum

The popularity of the Klout system attracted attention from more than venture capitalists, however. Celebrities wanted in on the act as they vied for their own form of social proof and an elite status among the Twitterati.

“We get quite a few e-mails and calls from companies and celebrities trying to raise their score,” Fernandez said. “We even got a call from the manager for Britney Spears. That was one of the first moments when it hit me as to where this might be going … the attention we were getting. I received an e-mail from her manager saying he was flying to San Francisco and wanted to meet me. It was a couple of people, him, a lawyer … they came by the office, we went out to lunch … and they really pressed me to know how to raise her Klout score. ‘Why is Britney’s Klout score lower than Lady Gaga’s and Ashton Kutcher’s?’ This meeting just blew me away. Here was this world-wide celebrity who was aware of her Klout score and wanted to understand it and know how to change it.”

“The timing is right for Klout,” Fernandez claimed. “The importance of social networking broadly for individuals and companies has reached a tipping point and we are in what I like to think of as an ‘attention economy.’ With Facebook, people started using their real names and as you start to use your own name online, your personal brand starts to matter. You can build your own influence like never before. All those things started happening around the same time Klout began its social credit score.”

In late 2010 the company piloted a monetization program called “Perks,” which allowed client companies to offer free gifts, discounts, upgrades and other benefits to influencers by topic. The initiative was incredibly successful, straining the start-up’s resources. Klout quadrupled its workforce in 12 months to keep up with demand.

Additional revenue began coming in from the nearly 3,000 API partners including Salesforce.com, The Huffington Post, and Hootsuite. Software programs using the Klout scores as part of their own product offerings make more than 2 billion “calls” to the Klout API every month.