By Mark Schaefer

About a year ago, I wrote a blog post that went against the grain. At a time when everybody was ga-ga over Snapchat I predicted that Facebook would eventually dismantle them. I wrote:

- Snapchat has no meaningful intellectual property. There is nothing really stopping Facebook (or the apps they own like Instagram, Messenger, or WhatsApp) from copying anything they do.

- Facebook already owns the hearts and minds of marketers. As Facebook responds to the Snapchat challenge they will be able to better serve advertisers and monetize more quickly.

- Facebook has virtually unlimited resources. They have more engineers, more money and more technology than Snapchat can imagine. Snapchat is going up against Goliath.

As Facebook aggressively “Snap-ifies” their properties day-by-day, it appears that I was correct in this forecast … but I’m sad about that. We are watching this amazing startup become copied piece-by-piece (largely because they refused to be swallowed up by Facebook in 2015).

Will Snapchat survive? Yes, in some measure. But they are losing both advertisers and users to Instagram and it seems unlikely they’ll be able to out-innovate Facebook for long-term success. Snapchat will probably become a marginal niche network like Twitter.

The message here seems to be … join the big company or die. And, as it turns out, this is exactly what is happening on a large-scale in America today.

End of the startup era?

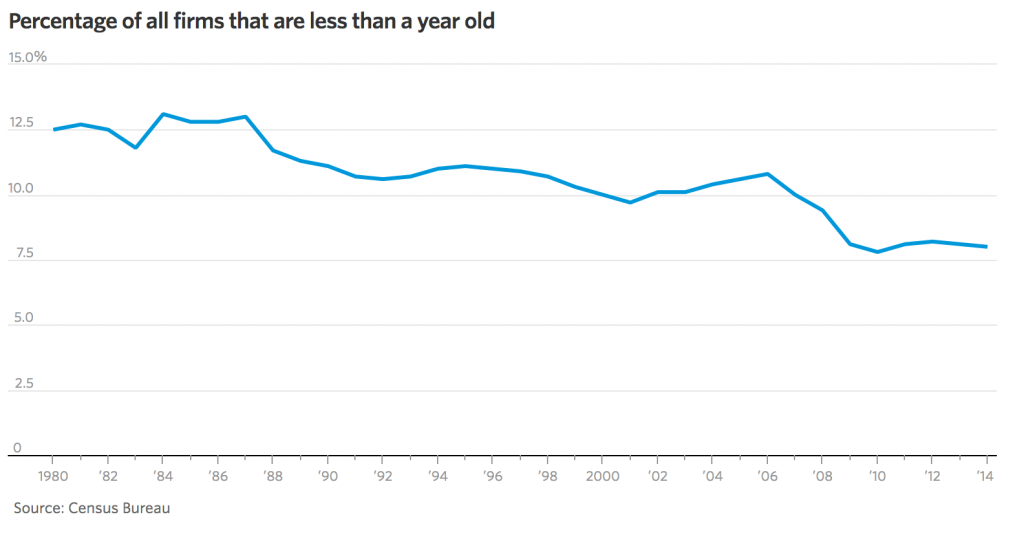

I’ve been thinking about how much more difficult it is today to grow a small company into a big one. The most dominant mega-companies are now on a continuous hunting mission to either destroy or acquire meaningful startups. In fact, the idea that we live in a start-economy is rapidly becoming a myth.

Here in the U.S., we pride ourselves in being a nation driven by entrepreneurs and small businesses. But the facts don’t bear that out any more.

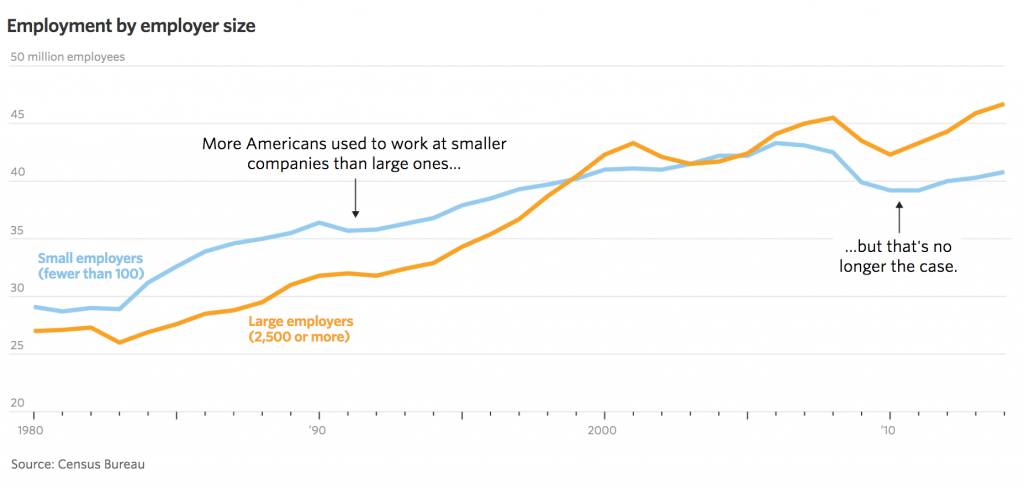

We are becoming a nation of employees working for large companies, often very large ones.

Huge companies dominate American economic life well beyond employment. They ring up a disproportionate share of sales for goods and services, both to consumers and to other businesses.

Scale alone isn’t bad. It can bring substantial efficiencies. National cellular providers can spare customers the complexity and expense of roaming charges.

At the same time, as big companies become bigger, they reinforce one another — “scale needs scale.” Big retailers prefer big distributors. Big manufacturers need big suppliers. Why would anyone take a risk on a start-up as a key supplier if you don’t have too? At the end of the day, people are risk averse, they make decisions that won’t get them fired.

The future of disruption

Over time, economists say, nimble new companies should form to challenge sprawling incumbents. As entrepreneurs, we revel in this dream of disruption, but it’s happening at a slower pace.

Young firms often fail or are absorbed by existing giants and business formation has slowed. In the past 12 months, Google alone has acquired 20 small companies including QuikLabs, Eyefluence and Urban Engines.

Another compelling fact pointing to the startup slowdown: There were 294 tech startups that raised $50 million apiece in 2014 and 2015, according to the Wall Street Journal. Almost three quarters of those companies — 216 — have neither raised money nor been acquired since the end of 2015. Startups tend to raise funding every 12 to 18 months.

I think part of this new economic reality is due to the fact that companies are more sensitive to their vulnerability to disruption than they were five or 10 years ago. For example, we see blue chip companies like Ford making proactive moves into alternative transportation modes (as they should).

Recently I interviewed the CTO of Dell EMC John Roese for a new podcast project called Luminaries (check it out!). I asked him if companies could rely on predictive models to tell where disruption could occur, and he said they could. Smart companies today can use algorithms to help them protect their flanks from disruptors.

For the past few years I have been playing around with this idea — what will eventually disrupt Facebook? After all, don’t all great ideas and companies eventually meet an end? I’m coming to the uncomfortable conclusion that the next Facebook will be Facebook as it continually absorbs, adapts … and sometimes copies … its way into the future.

In a New York Times editorial, Jonathan Taplin argues that the biggest tech giants should be considered monopolies, and that it’s time to break them up:

In just 10 years, the world’s five largest companies by market capitalization have all changed, save for one: Microsoft. Exxon Mobil, General Electric, Citigroup and Shell Oil are out and Apple, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Amazon and Facebook have taken their place.

They’re all tech companies, and each dominates its corner of the industry: Google has an 88 percent market share in search advertising, Facebook (and its subsidiaries Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger) owns 77 percent of mobile social traffic and Amazon has a 74 percent share in the e-book market. In classic economic terms, all three are monopolies.

We have been in a glorious era where disruptive little fish could eat the big fish. Is that time coming to a close? What are your thoughts?

Some of the data and insights for this post came from a Wall Street Journal article entitled Why you probably work for a giant company. I have subscribed continuously to the WSJ since I was 21 years old and I encourage you to subscribe too to support their journalistic mission.

Mark Schaefer is the chief blogger for this site, executive director of Schaefer Marketing Solutions, and the author of several best-selling digital marketing books. He is an acclaimed keynote speaker, college educator, and business consultant. The Marketing Companion podcast is among the top business podcasts in the world. Contact Mark to have him speak to your company event or conference soon.

Mark Schaefer is the chief blogger for this site, executive director of Schaefer Marketing Solutions, and the author of several best-selling digital marketing books. He is an acclaimed keynote speaker, college educator, and business consultant. The Marketing Companion podcast is among the top business podcasts in the world. Contact Mark to have him speak to your company event or conference soon.