By Jay Acunzo, {grow} Community Member

TL;DR—Influencer marketing is a big and growing trend, but few organizations are reaping the biggest possible rewards of the approach. Let’s reset our thinking, so we can improve our results.

When a new trend starts careening towards ubiquity, the pundits beat their blogs for blood—declaring victors in a battle they imagine is real:

“Email is dead. Social media won!”

“It’s the era of video. Text is doomed!”

“Here comes Ello. Will it kill Facebook? lol jk no way…”

(Sorry. I STILL can’t resist taking a shot at Ello.)

While these are fun debates, reality is always murkier. It’s hard to see clearly thanks to this grainy, gritty, boring substance called “nuance.”

But if an organization wants to capitalize, they must be more nuanced in their understanding of new trends than what the blogosphere would have us believe.

And today, the business blogosphere would have us believe that influencer marketing is all about that old addicting drug brands so crave: reach. But believe you me, the quickest way to minimize the potential of your influencer marketing is to treat individual creators like mini media companies.

In other words, while media companies are great for pure reach and awareness, influencers bring a whole separate set of benefits to your brand.

As soon as a marketer approaches an influencer with total audience size or CPMs in mind, both sides have lost.

Let’s sift through that grainy, nuanced reality for a bit…

Media Companies and Influencers Are Different but Complementary

Consider the marketing funnel for a moment, but instead of purchase behavior, let’s describe it based on consumer attention—the most precious commodity in today’s hyperactive, noisy world.

As a marketer, you can ACQUIRE, RETAIN, or CONVERT attention. In the end, the goal is to own the LOYALTY of an audience that adores, buys from, and shares your brand.

Media publishers are best at acquiring attention, while influencers dominate at retaining it. In other words:

Publishers excel at reach, while influencers win on relationships.

If this is true, then the two groups are complementary, serving different purposes to brands based on what they hope to achieve. And it’s all caused by their differing incentives and business models.

The Power of Publishers

Media companies ranging from the Times and WaPo to niche magazines and blogs create content to generate reach. This can be either absolute, unbounded reach (the Times wants all of humanity consuming their stuff) or more focused reach (a magazine about software sales wants all software salespeople consuming their stuff).

To make money on a publication’s reach, a media company doesn’t need the audience to be all that active. It takes very little effort for a reader to count as a “view” or “impression,” after all. However, the publisher benefits greatly from that passive audience, as they sell their impression count to marketers who buy banner ads, video ads, sponsored content, and the like.

We can debate the pros and cons of a reach-driven, impression-based business model another time, but for now, it’s fair to say that the vast majority of publishers make their money based on growing big audiences rather than asking that audience to take actions.

Brands need both reach and actions, and so publishers are useful partners for growing reach, but the onus for converting action is then on the brand.

But this is a poor approach to working with influencers.

The Influence of Individual Creators

An individual creator can’t rely on reach. Instead, he or she is incentivized to develop genuine relationships with their readers or followers, as the influencer often sell products or services. If they don’t, then they typically build a series of content together with brands as the underwriters, and those brands want to see “engagement” beyond “impressions.”

I’ll use my own model as an example.

As soon as a potential partner mentions CPMs, I know it’s a bad fit. My weekly show is not built to generate the biggest and fastest-growing topline number. It’s meant to resonate deeply with an audience and trigger actions—leads for my speaking or requests to host/produce shows of a similar quality and similar differentiation for other brands (like this one).

My show is also meant to test and tinker on a big idea, and the stories to support the idea, all of which can become a methodology to productize and teach, as well as include in an eventual book.

The common thread in all of this is simple, and far different from a media company: I’m focused on depth, not breadth. I need my audience to take real actions beyond just consuming my stuff—email me, talk to me on phone calls (which I hold monthly with my audience), attend events, buy my eventual courses or book.

Rather than reach, I’m focused on resonance.

I’m a lousy partner if a marketer’s goal is absolute or net-new attention. But I’m a superior partner than a media company if a marketer wants to be memorable, make an impact, and trigger real actions from superfans.

To achieve the latter, I work with brands in one of two ways, both centered on the production of a pillar content series (podcast, video, columns, etc.):

- CO-OWNED SERIES—We target the same audiences, so a partner cares about audience access and also how I create depth of attention with that audience. As a result, we work together on content we both own.

In my case, the Content Marketing Institute approached me to co-create a mini-series of podcast episodes—a sort of “Inside the Actor’s Studio”-style interview series with key content marketing influencers. The episodes run inside my own show and are promoted in my newsletter and on social, while CMI does the same. It is billed as “Unthinkable + CMI” to the public, and CMI benefits from my ideas, process, and direct audience access.

- A BRAND-OWNED SERIES—A partner targets a different audience than mine, so they care less about audience access and more about HOW I create depth of attention. As a result, we work together on something you and you alone will own.

In my case, Social Media Examiner tapped me to produce a behind-the-scenes documentary series about their big annual event. They already had reach via their weekly show, the Social Media Marketing podcast, so they ran the stories I produced within their episodes. Beyond a few shares from me as the proud producer, I didn’t actively promote this series. It didn’t appear in my Unthinkable show, newsletter, or social feeds, as the message and content wouldn’t make sense. The series was branded as Social Media Examiner’s, not as “Unthinkable + SME.” In this case, SME benefitted from my ideas and process, but they did not care about accessing my audience.

In any and all cases such as these, marketers should work with individual creators or influencers for depth—total time spent, engagement, passive-to-active conversions (e.g. view-to-subscriber; subscriber re-engagement) and so forth.

The power of influencer marketing isn’t a transaction. It’s not borrowed attention. It’s the partnership. It’s what you COULD DO over time, together, as partners. This focus on resonance and relationships with an audience makes the rest of your marketing work harder for you. It’s the protein in your smoothie. The Mentos in your Coke bottle. The, uh … the steroid in your butt cheek?

But, you know: a legal one. And more pleasant.

In this distracted media landscape, individual creators can succeed and be useful to brands by being what could be misconstrued as a limitation: a person.

The Time Is Now

What if marketers evolved from being in constant Acquisition Mode to Retention Mode? We all say it’s better to retain an existing customer than acquire a new one. The data shows it. The precedents are there. And then we spend all our time thinking about net-new reach. We obsess over breadth.

What about depth? What about, in a word, trust?

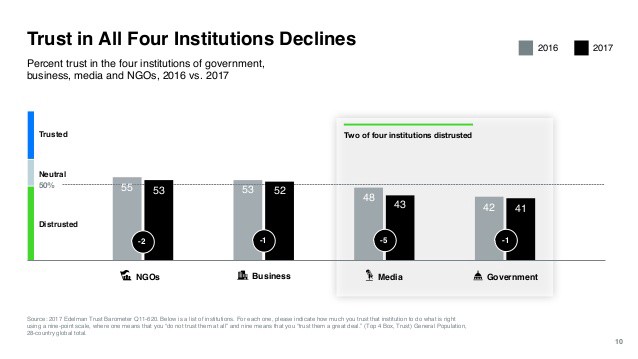

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, trust is down across the board in the four big institutions:

According to the Harvard Business Review, this is the first time we’ve seen that kind of decline in 17 years.

Furthermore, Big Media—so often the source of a marketer’s future tactics—are already reacting to this troubling trend by working more closely with individual creators:

- CNN is pushing more personalities like Anthony Bourdain or YouTube sensation Casey Neistat.

- HBO recently partnered with ex-ESPN columnist Bill Simmons to produce new shows on the web and through HBO’s streaming services. Simmons in turn is recruiting other, smaller influencers in sports and pop culture, like the intellectual TV critic Andy Greenwald or bombastic NBA podcast host Chris Vernon.

- ESPN gave Scott Van Pelt his own SportsCenter, followed by Michael Smith and Jemele Hill. Both shows have logos developed around the personalities. All three people are featured heavily in ad spots for their shows. And this is after years of John A. Walsh, “Godfather of SportsCenter,” resisting and even firing people over his insistence that the network is more important than the individual personality.

Innovative product companies are just now starting to adopt a similar approach. Salesforce hired Vala Afshar. Canva tapped Guy Kawasaki. GetResponse works with Michael Brenner. Each is betting more heavily on the individual influencer’s ability to generate depth of attention.

If you’re a brand thinking of using influencers in your marketing, the choices should be clear:

- Work with publishers if your goal is broad reach or net-new audience. You then own the conversion of that reach into depth and action.

- Work with influencers if your goal is deep resonance or a passionate and active audience. You then own the amplification of that passion (and the influencer can help kickstart it).

Do you need reach or resonance? Awareness or trust? One moment in time or a relationship over time?

In this gritty, grainy, nuanced view of modern marketing, the answer is surprisingly clear: Pursue both. But pick the right partner for each.

Jay Acunzo is a keynote speaker and award-winning show host. Formerly of Google and HubSpot, his weekly podcast, Unthinkable, tells stories of marketers who break from conventional thinking.

Jay Acunzo is a keynote speaker and award-winning show host. Formerly of Google and HubSpot, his weekly podcast, Unthinkable, tells stories of marketers who break from conventional thinking.

Illustration courtesy Flickr CC and Steven Jackson